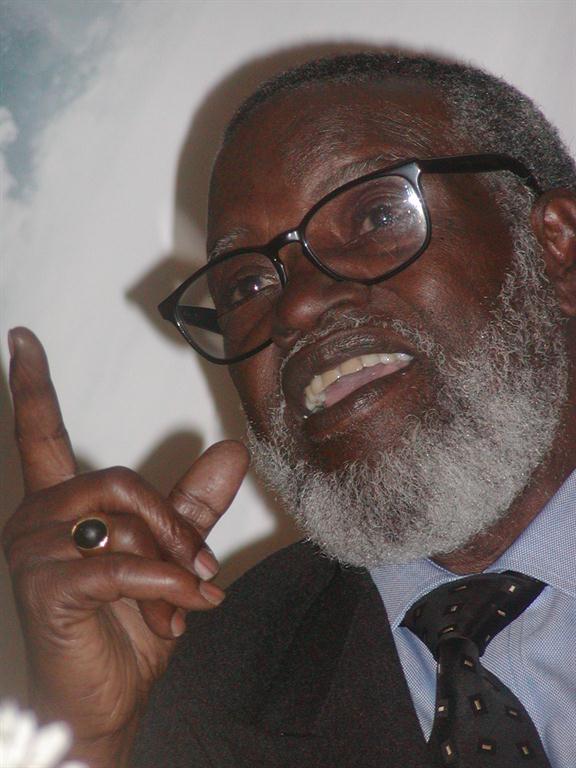

The man behind the legend

Life and times of Sam Shafiishuna Nujoma

Sam Nujoma led Swapo since its formation in 1960 until 2007.

After 29 years in exile, he returned to Namibia in September 1989 to lead Swapo to victory in the UN-supervised elections that paved the way for independence.

The Constituent Assembly, elected in November 1989, chose him as Namibia's first President and he was sworn in on Independence Day, March 21 1990. In Namibia's first presidential election in 1994 he won 74 percent of the vote. Five years later, after the Constitution was changed to allow Nujoma to stand for a third term, his share of the vote increased to 77 percent, slightly in excess of Swapo's popularity. He finished his third term in office in March 2005 and handed over power to his preferred successor, Hifikepunye Pohamba. Two years later he stood down as President of the ruling party.

Nujoma was born at Etunda in the Omusati region on May 12 1929. He spent much of his early childhood looking after his siblings and tending to the family's cattle. Educational opportunities were limited. He started attending a Finnish missionary school at Okahao when he was ten and completed Standard Six. In 1946, when he was 17, he went to live with an aunt in Walvis Bay, where he worked in a general store and then at a whaling station. The young Nujoma moved to Windhoek in 1949 and started work as a cleaner for the South African Railways (SAR), while attending night classes and undertaking a correspondence course, mainly with the aim of improving his English.

He married Kovambo Katjimune in 1956 and the couple were to have three sons and a daughter, all born before Nujoma went into exile in early 1960 (two decades elapsed before his wife joined him abroad). In the late 1950s Nujoma's political outlook was shaped by his work experiences, his awareness of the contract labour system, and his increasing knowledge of the independence campaigns across Africa. In 1957, at the age of 29, he resigned from SAR so he could devote more time to politics.

From OPO to Swapo

On April 19 1959 Ovamboland People's Organisation (OPO) was formed with the dual aims of ending the contract labour system and having the then South West Africa placed under a UN trusteeship. Nujoma was the OPO's first and only president. During the next year Nujoma travelled the country, often in secret, to spread the word about OPO.

In September 1959 he joined the executive committee of the South West Africa National Union (Swanu), which at the time was seen as an umbrella body for anti-colonial resistance groups, including OPO. Nujoma was at the forefront of the campaign against the forced removal of inhabitants of Windhoek's Old Location to Katutura. Matters came to a head on December 10 1959 when the police opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing 12 people.

In the wake of the shootings, Nujoma faced the threat of deportation to the north of the country as the authorities clamped down on the incipient nationalist movement. In February 1960 OPO decided that Nujoma should leave the country to join those Namibians already lobbying at the UN for Namibia's self-determination. Nujoma had already petitioned the UN through letters also signed by Oerero Chief Hosea Kutako and Nama Chief Samuel Witbooi.

Nujoma left Namibia on February 29 1960, crossing into Botswana (then Bechuanaland) and from there, using the false name of David Chipinga, travelling to Bulawayo by train. He flew from Bulawayo, then in Southern Rhodesia, to Salisbury (now Harare) and on to Ndola. Finally he arrived in Mbeya in eastern Tanzania, which was still the British colony of Tanganyika, on March 21 1960. While in Tanzania he received permission to address the UN Committee on South West Africa in New York.

Nujoma arrived in independent Ghana in April 1960 and met President Kwame Nkrumah, among other African leaders. His early encounters with the likes of Nkrumah and Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt left a lasting impression and informed his pan-African outlook. From Ghana he moved to Liberia where the decision was taken to give OPO a national character by changing its name to the South West Africa People's Organisation (Swapo). Nujoma was confirmed as president of the reconstituted movement. He arrived in New York in June and stayed for the rest of the year. He petitioned the UN several times, arguing that South West Africa should be given its independence by 1963 at the latest.

Armed struggle

In early 1961 Nujoma returned to Tanzania, from where he and a small group of activists would develop Swapo into an international force within a decade. As the only Namibian in Dar es Salaam, Nujoma looked for support from other African nationalists and received strong backing from Julius Nyerere, the future leader of the East African country.

Nujoma established Swapo's Provisional HQ in Dar es Salaam and arranged scholarships and military training for Namibians who had started to join him there. Among the first arrivals were Simon Mzee Kaukungwa, Mosé Tjitendero, Hifikepunye Pohamba and Nickey Iyambo. He also attended numerous international conferences and his diplomatic forays started to pay off when the OAU recognised Swapo in 1965. From the early 1960s Swapo planned to launch an armed struggle. Nujoma himself procured the first weapons from Algeria. Before the fighting commenced, Nujoma, accompanied by Pohamba, decided to challenge the South African assertion that they were in self-imposed exile by returning to Windhoek. They flew in on March 21 1966, only to be arrested on arrival and deported sixteen hours later.

On August 26 1966 the first armed clash of the liberation struggle took place when the South African police attacked Swapo combatants who had set up a camp at Omugulu-gOmbashe. At the end of 1969 Nujoma was re-affirmed as Swapo President at the Tanga Consultative Conference in Tanzania.

In the late 1960s Nujoma continued his diplomatic rounds as Swapo set up offices across Africa, Europe and the Americas. Although ostensibly based in Zambia from the early 1970s (after Swapo moved its HQ to Lusaka), Nujoma was living out of a suitcase for much of the time.

He acknowledged in his autobiography that he “spent a large part of each year in hotel rooms and conference halls” (Where Others Wavered, Nujoma 2001: 198). A diplomatic breakthrough came in October 1971 when Nujoma became the first African liberation movement leader to address the UN Security Council. This international campaigning bore further fruit at the end of 1973 when the UN General Assembly recognised Swapo as the “authentic representative of the Namibian people”.

In 1975 one of Namibia's earliest petitioners at the UN, Jariretundu Kozonguizi, attributed Swapo's success on the world stage to Nujoma's dynamism: “Their [Swapo's] single advantage has been in the single-mindedness and presence in their lobby of the person of their President. It is not an exaggeration to say that during the last 15 years he had hardly spent a month in one place” (quoted in Nujoma 2001: 243).

Challenging times

In 1974 the Portuguese empire collapsed and Namibia's border with Angola opened up. Nujoma recognised that this paved the way for major changes in the way the war was being fought and over the next two years Swapo's military campaign shifted its base from Zambia to Angola. The opening of the border enabled thousands of Swapo supporters to stream out of Namibia to join the movement in exile. Nujoma's three sons were among those who arrived in Zambia (his daughter had died while still an infant).

The sudden upsurge in the numbers leaving the country precipitated a major challenge to Nujoma's authority. Among the exodus were Swapo Youth League (SYL) activists who arrived in Zambia with high expectations and were soon seeking representation in Swapo's structures and a congress to review the movement's progress. Their demands coincided with unrest among People's Liberation Army of Namibia (Plan) recruits in Western Zambia who complained of logistical problems and wanted better food and more weapons. The Swapo leadership called in the Zambian army to put down the rebellion. Several SYL activists and some well-known Swapo leaders such as Andreas Shipanga were arrested in Lusaka and ultimately sent to Tanzania, where they were imprisoned until 1977. Over a thousand Plan combatants were held at the Mboroma camp near Kabwe – an unknown number were killed, while the rest eventually opted either to rejoin Swapo or leave the movement.

Nujoma put the blame for the crisis on the shoulders of Shipanga and other unknown “infiltrators” ( Nujoma 2001: 246). In the 1980s hundreds of Namibians who joined Swapo in exile would also be accused of being enemy agents. They were detained and tortured at Lubango in southern Angola by Swapo's security apparatus. Even Nujoma's wife, Kovambo, was eventually caught up in the paranoia about enemy infiltration and placed under house arrest at Lubango in 1988. The former detainees have accused Nujoma of failing to challenge the security chiefs within Swapo, including the reviled 'Butcher of Lubango', Solomon Hawala (who Nujoma later appointed as the head of the Namibian Defence Force). Nujoma visited the detention camps but ignored the prisoners' complaints of torture and mistreatment.

In the late 1970s Nujoma led the Swapo delegation to talks with the Western Contact Group (West Germany, Britain, France, USA and Canada) about proposals that would eventually become UN Security Council Resolution 435, passed in September 1978. While agreement on Resolution 435, which embodied the plan for free and fair elections in Namibia, was undoubtedly a diplomatic coup, its implementation became bogged down for another ten years. South African delaying tactics and the US Reagan administration's decision to link a Cuban withdrawal from Angola to Namibia independence frustrated hopes of an immediate settlement and it was not until September 14 1989 that Nujoma returned to a hero's welcome from Swapo supporters at Windhoek's international airport.

Nujoma's long exile, rather than diminishing his importance inside Namibia, had resulted in him becoming a near-mythic figure for many. He was greeted at the airport by his 89-year-old mother (Helvi Mpingana Kondombolo, who died in 2008) and the rest of the Swapo leadership. He immediately hit the campaign trail, as the UN-supervised elections were only two months away.

Independence arrives

Swapo's success in that initial election (gaining 57 percent support) has been eclipsed by its share of the vote since then. Nujoma's approach to politics has been pragmatic rather than ideological. While he has been at pains to give credit to the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc for aiding Swapo during the struggle, he has also been keen to point out that he was never a Marxist-Leninist and that perceptions of Swapo as a communist movement were wrongheaded.

At independence he declared a policy of national reconciliation and his first Cabinet reflected a policy of 'One Namibia, One Nation' rather than hardline Swapo politics (including opposition members as deputy ministers and whites no previously closely associated with the ruling party). The policy undoubtedly helped consolidate peace in Namibia - although critics would argue that ultimately it led to only limited land reform and a lack of radical measures to address inequality and poverty that resulted from apartheid colonialism. One of the abiding themes in his speeches after independence has been his belief in pan-Africanism and the quest against imperialism. Many of his words echo the nationalist statements he made on behalf of Swapo some 40 years ago. In 1998 Nujoma came to the defence of DRC President Laurent Kabila when his rule came under threat from rebels backed by Rwanda and Uganda. Namibian, Angolan and Zimbabwean troops helped Kabila fend off the attacks – a move which Nujoma saw as defending the DRC's sovereignty against outside interference. Equally controversial was his decision to allow Angolan troops to launch attacks in the late 1990s from within Namibia on the rebel movement Unita led by Jonas Savimbi.

Nujoma commands great loyalty and finds it hard to tolerate anything that might be seen as disloyalty. Those who have crossed him are liable to join his list of traitors – which includes Shipanga, Muyongo, and Savimbi.

Nujoma's presidency, especially from the mid-1990s onwards, was peppered with angry outbursts – during which 'homosexuals', 'Boers', and 'imperialists' were often lambasted. Such attacks and his close relationship with President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe occupied many of the column inches about Namibia in the international press, which often portrayed Nujoma as a proto-Mugabe figure, even though there were major differences between the two countries' land policies and approaches to human rights.

In private

While he is known for his sharp rejection of those he perceives as undermining Swapo, Namibia, or Africa, he has also gone to great trouble to keep different interest groups on board – within the party structures, Cabinet, and parliament. Very few ministers were dropped, although the dismissals of Hage Geingob in 2002 and Hidipo Hamutenya in 2004 did indicate that even senior party figures could fall into disfavour if they were seen to be challenging Nujoma's will on crucial issues. It is difficult to separate Nujoma's personal story from the history of Swapo and the struggle for Namibian independence. Attempts to uncover the private Nujoma have never revealed much more than that his favourite books are ones that deal with politics and economics (he never reads fiction, saying it is a waste of time) and that liberation songs from the struggle are his music of choice. During his time in State House, his shortwave radio was never far from his side – tuned into the NBC and news broadcasts from around the world, reflecting how he kept in touch during the struggle years.

Nujoma's formidable energy and abstemiousness (he spurns luxurious living) helped win him levels of support that went much wider than Swapo's core base. His willingness to get his hands dirty in the cause of development also broadened his appeal.

His trademark dynamism remained undimmed during his 15 years as head of state, as can be witnessed from his personal involvement in the construction of the Tsumeb-Oshikango railway line during his last term in office.

Once it was clear that he had decided not to seek another term in office, Nujoma set his sights on ensuring that his chosen successor, Hifikepunye Pohamba, would win the nomination to be Swapo's presidential candidate in the 2004 elections. Swapo decided to hold a special congress to select a candidate from three contenders – Pohamba, Hamutenya and Nahas Angula – in May 2004. In a move that would open up faultlines in the party, Nujoma sacked Hamutenya as his Foreign Minister just days before the congress.

The effect of the sacking was to diminish Hamutenya's chances of overcoming Nujoma's chosen candidate. In the end Pohamba won the nomination after a second round of voting and would cruise to victory in the presidential elections later in the year.

In 2001, his autobiography, Where Others Wavered: My Life in Swapo and My Participation in the Liberation Struggle of Namibia, was published by Panaf. In 2007 a film based on the book was released.

He served as the Chancellor of the University of Namibia (Unam) from1993 until 2011. In late 2005, Nujoma was accorded the official title 'Founding Father of the Namibian Nation' through an Act of parliament. In the same year, the Sam Nujoma Foundation was set up in his honour. In 2009, Nujoma received a master's degree in Geology from the University of Namibia.

Although the amount of political influence Nujoma has wielded after his time in power is still a matter of debate, he has said very little in public regarding the state of the nation or Swapo's internal politics.

In 2012 he did not publicly endorse any candidate at a congress to choose a new Swapo presidential candidate.

He took the same stance at the 2017 Swapo congress, declining to explicitly endorse candidates. In 2015, President Geingob asked Nujoma to serve on the new presidential advisory council.

* Adapted and updated from the Guide to Namibian Politics by Graham Hopwood

After 29 years in exile, he returned to Namibia in September 1989 to lead Swapo to victory in the UN-supervised elections that paved the way for independence.

The Constituent Assembly, elected in November 1989, chose him as Namibia's first President and he was sworn in on Independence Day, March 21 1990. In Namibia's first presidential election in 1994 he won 74 percent of the vote. Five years later, after the Constitution was changed to allow Nujoma to stand for a third term, his share of the vote increased to 77 percent, slightly in excess of Swapo's popularity. He finished his third term in office in March 2005 and handed over power to his preferred successor, Hifikepunye Pohamba. Two years later he stood down as President of the ruling party.

Nujoma was born at Etunda in the Omusati region on May 12 1929. He spent much of his early childhood looking after his siblings and tending to the family's cattle. Educational opportunities were limited. He started attending a Finnish missionary school at Okahao when he was ten and completed Standard Six. In 1946, when he was 17, he went to live with an aunt in Walvis Bay, where he worked in a general store and then at a whaling station. The young Nujoma moved to Windhoek in 1949 and started work as a cleaner for the South African Railways (SAR), while attending night classes and undertaking a correspondence course, mainly with the aim of improving his English.

He married Kovambo Katjimune in 1956 and the couple were to have three sons and a daughter, all born before Nujoma went into exile in early 1960 (two decades elapsed before his wife joined him abroad). In the late 1950s Nujoma's political outlook was shaped by his work experiences, his awareness of the contract labour system, and his increasing knowledge of the independence campaigns across Africa. In 1957, at the age of 29, he resigned from SAR so he could devote more time to politics.

From OPO to Swapo

On April 19 1959 Ovamboland People's Organisation (OPO) was formed with the dual aims of ending the contract labour system and having the then South West Africa placed under a UN trusteeship. Nujoma was the OPO's first and only president. During the next year Nujoma travelled the country, often in secret, to spread the word about OPO.

In September 1959 he joined the executive committee of the South West Africa National Union (Swanu), which at the time was seen as an umbrella body for anti-colonial resistance groups, including OPO. Nujoma was at the forefront of the campaign against the forced removal of inhabitants of Windhoek's Old Location to Katutura. Matters came to a head on December 10 1959 when the police opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing 12 people.

In the wake of the shootings, Nujoma faced the threat of deportation to the north of the country as the authorities clamped down on the incipient nationalist movement. In February 1960 OPO decided that Nujoma should leave the country to join those Namibians already lobbying at the UN for Namibia's self-determination. Nujoma had already petitioned the UN through letters also signed by Oerero Chief Hosea Kutako and Nama Chief Samuel Witbooi.

Nujoma left Namibia on February 29 1960, crossing into Botswana (then Bechuanaland) and from there, using the false name of David Chipinga, travelling to Bulawayo by train. He flew from Bulawayo, then in Southern Rhodesia, to Salisbury (now Harare) and on to Ndola. Finally he arrived in Mbeya in eastern Tanzania, which was still the British colony of Tanganyika, on March 21 1960. While in Tanzania he received permission to address the UN Committee on South West Africa in New York.

Nujoma arrived in independent Ghana in April 1960 and met President Kwame Nkrumah, among other African leaders. His early encounters with the likes of Nkrumah and Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt left a lasting impression and informed his pan-African outlook. From Ghana he moved to Liberia where the decision was taken to give OPO a national character by changing its name to the South West Africa People's Organisation (Swapo). Nujoma was confirmed as president of the reconstituted movement. He arrived in New York in June and stayed for the rest of the year. He petitioned the UN several times, arguing that South West Africa should be given its independence by 1963 at the latest.

Armed struggle

In early 1961 Nujoma returned to Tanzania, from where he and a small group of activists would develop Swapo into an international force within a decade. As the only Namibian in Dar es Salaam, Nujoma looked for support from other African nationalists and received strong backing from Julius Nyerere, the future leader of the East African country.

Nujoma established Swapo's Provisional HQ in Dar es Salaam and arranged scholarships and military training for Namibians who had started to join him there. Among the first arrivals were Simon Mzee Kaukungwa, Mosé Tjitendero, Hifikepunye Pohamba and Nickey Iyambo. He also attended numerous international conferences and his diplomatic forays started to pay off when the OAU recognised Swapo in 1965. From the early 1960s Swapo planned to launch an armed struggle. Nujoma himself procured the first weapons from Algeria. Before the fighting commenced, Nujoma, accompanied by Pohamba, decided to challenge the South African assertion that they were in self-imposed exile by returning to Windhoek. They flew in on March 21 1966, only to be arrested on arrival and deported sixteen hours later.

On August 26 1966 the first armed clash of the liberation struggle took place when the South African police attacked Swapo combatants who had set up a camp at Omugulu-gOmbashe. At the end of 1969 Nujoma was re-affirmed as Swapo President at the Tanga Consultative Conference in Tanzania.

In the late 1960s Nujoma continued his diplomatic rounds as Swapo set up offices across Africa, Europe and the Americas. Although ostensibly based in Zambia from the early 1970s (after Swapo moved its HQ to Lusaka), Nujoma was living out of a suitcase for much of the time.

He acknowledged in his autobiography that he “spent a large part of each year in hotel rooms and conference halls” (Where Others Wavered, Nujoma 2001: 198). A diplomatic breakthrough came in October 1971 when Nujoma became the first African liberation movement leader to address the UN Security Council. This international campaigning bore further fruit at the end of 1973 when the UN General Assembly recognised Swapo as the “authentic representative of the Namibian people”.

In 1975 one of Namibia's earliest petitioners at the UN, Jariretundu Kozonguizi, attributed Swapo's success on the world stage to Nujoma's dynamism: “Their [Swapo's] single advantage has been in the single-mindedness and presence in their lobby of the person of their President. It is not an exaggeration to say that during the last 15 years he had hardly spent a month in one place” (quoted in Nujoma 2001: 243).

Challenging times

In 1974 the Portuguese empire collapsed and Namibia's border with Angola opened up. Nujoma recognised that this paved the way for major changes in the way the war was being fought and over the next two years Swapo's military campaign shifted its base from Zambia to Angola. The opening of the border enabled thousands of Swapo supporters to stream out of Namibia to join the movement in exile. Nujoma's three sons were among those who arrived in Zambia (his daughter had died while still an infant).

The sudden upsurge in the numbers leaving the country precipitated a major challenge to Nujoma's authority. Among the exodus were Swapo Youth League (SYL) activists who arrived in Zambia with high expectations and were soon seeking representation in Swapo's structures and a congress to review the movement's progress. Their demands coincided with unrest among People's Liberation Army of Namibia (Plan) recruits in Western Zambia who complained of logistical problems and wanted better food and more weapons. The Swapo leadership called in the Zambian army to put down the rebellion. Several SYL activists and some well-known Swapo leaders such as Andreas Shipanga were arrested in Lusaka and ultimately sent to Tanzania, where they were imprisoned until 1977. Over a thousand Plan combatants were held at the Mboroma camp near Kabwe – an unknown number were killed, while the rest eventually opted either to rejoin Swapo or leave the movement.

Nujoma put the blame for the crisis on the shoulders of Shipanga and other unknown “infiltrators” ( Nujoma 2001: 246). In the 1980s hundreds of Namibians who joined Swapo in exile would also be accused of being enemy agents. They were detained and tortured at Lubango in southern Angola by Swapo's security apparatus. Even Nujoma's wife, Kovambo, was eventually caught up in the paranoia about enemy infiltration and placed under house arrest at Lubango in 1988. The former detainees have accused Nujoma of failing to challenge the security chiefs within Swapo, including the reviled 'Butcher of Lubango', Solomon Hawala (who Nujoma later appointed as the head of the Namibian Defence Force). Nujoma visited the detention camps but ignored the prisoners' complaints of torture and mistreatment.

In the late 1970s Nujoma led the Swapo delegation to talks with the Western Contact Group (West Germany, Britain, France, USA and Canada) about proposals that would eventually become UN Security Council Resolution 435, passed in September 1978. While agreement on Resolution 435, which embodied the plan for free and fair elections in Namibia, was undoubtedly a diplomatic coup, its implementation became bogged down for another ten years. South African delaying tactics and the US Reagan administration's decision to link a Cuban withdrawal from Angola to Namibia independence frustrated hopes of an immediate settlement and it was not until September 14 1989 that Nujoma returned to a hero's welcome from Swapo supporters at Windhoek's international airport.

Nujoma's long exile, rather than diminishing his importance inside Namibia, had resulted in him becoming a near-mythic figure for many. He was greeted at the airport by his 89-year-old mother (Helvi Mpingana Kondombolo, who died in 2008) and the rest of the Swapo leadership. He immediately hit the campaign trail, as the UN-supervised elections were only two months away.

Independence arrives

Swapo's success in that initial election (gaining 57 percent support) has been eclipsed by its share of the vote since then. Nujoma's approach to politics has been pragmatic rather than ideological. While he has been at pains to give credit to the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc for aiding Swapo during the struggle, he has also been keen to point out that he was never a Marxist-Leninist and that perceptions of Swapo as a communist movement were wrongheaded.

At independence he declared a policy of national reconciliation and his first Cabinet reflected a policy of 'One Namibia, One Nation' rather than hardline Swapo politics (including opposition members as deputy ministers and whites no previously closely associated with the ruling party). The policy undoubtedly helped consolidate peace in Namibia - although critics would argue that ultimately it led to only limited land reform and a lack of radical measures to address inequality and poverty that resulted from apartheid colonialism. One of the abiding themes in his speeches after independence has been his belief in pan-Africanism and the quest against imperialism. Many of his words echo the nationalist statements he made on behalf of Swapo some 40 years ago. In 1998 Nujoma came to the defence of DRC President Laurent Kabila when his rule came under threat from rebels backed by Rwanda and Uganda. Namibian, Angolan and Zimbabwean troops helped Kabila fend off the attacks – a move which Nujoma saw as defending the DRC's sovereignty against outside interference. Equally controversial was his decision to allow Angolan troops to launch attacks in the late 1990s from within Namibia on the rebel movement Unita led by Jonas Savimbi.

Nujoma commands great loyalty and finds it hard to tolerate anything that might be seen as disloyalty. Those who have crossed him are liable to join his list of traitors – which includes Shipanga, Muyongo, and Savimbi.

Nujoma's presidency, especially from the mid-1990s onwards, was peppered with angry outbursts – during which 'homosexuals', 'Boers', and 'imperialists' were often lambasted. Such attacks and his close relationship with President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe occupied many of the column inches about Namibia in the international press, which often portrayed Nujoma as a proto-Mugabe figure, even though there were major differences between the two countries' land policies and approaches to human rights.

In private

While he is known for his sharp rejection of those he perceives as undermining Swapo, Namibia, or Africa, he has also gone to great trouble to keep different interest groups on board – within the party structures, Cabinet, and parliament. Very few ministers were dropped, although the dismissals of Hage Geingob in 2002 and Hidipo Hamutenya in 2004 did indicate that even senior party figures could fall into disfavour if they were seen to be challenging Nujoma's will on crucial issues. It is difficult to separate Nujoma's personal story from the history of Swapo and the struggle for Namibian independence. Attempts to uncover the private Nujoma have never revealed much more than that his favourite books are ones that deal with politics and economics (he never reads fiction, saying it is a waste of time) and that liberation songs from the struggle are his music of choice. During his time in State House, his shortwave radio was never far from his side – tuned into the NBC and news broadcasts from around the world, reflecting how he kept in touch during the struggle years.

Nujoma's formidable energy and abstemiousness (he spurns luxurious living) helped win him levels of support that went much wider than Swapo's core base. His willingness to get his hands dirty in the cause of development also broadened his appeal.

His trademark dynamism remained undimmed during his 15 years as head of state, as can be witnessed from his personal involvement in the construction of the Tsumeb-Oshikango railway line during his last term in office.

Once it was clear that he had decided not to seek another term in office, Nujoma set his sights on ensuring that his chosen successor, Hifikepunye Pohamba, would win the nomination to be Swapo's presidential candidate in the 2004 elections. Swapo decided to hold a special congress to select a candidate from three contenders – Pohamba, Hamutenya and Nahas Angula – in May 2004. In a move that would open up faultlines in the party, Nujoma sacked Hamutenya as his Foreign Minister just days before the congress.

The effect of the sacking was to diminish Hamutenya's chances of overcoming Nujoma's chosen candidate. In the end Pohamba won the nomination after a second round of voting and would cruise to victory in the presidential elections later in the year.

In 2001, his autobiography, Where Others Wavered: My Life in Swapo and My Participation in the Liberation Struggle of Namibia, was published by Panaf. In 2007 a film based on the book was released.

He served as the Chancellor of the University of Namibia (Unam) from1993 until 2011. In late 2005, Nujoma was accorded the official title 'Founding Father of the Namibian Nation' through an Act of parliament. In the same year, the Sam Nujoma Foundation was set up in his honour. In 2009, Nujoma received a master's degree in Geology from the University of Namibia.

Although the amount of political influence Nujoma has wielded after his time in power is still a matter of debate, he has said very little in public regarding the state of the nation or Swapo's internal politics.

In 2012 he did not publicly endorse any candidate at a congress to choose a new Swapo presidential candidate.

He took the same stance at the 2017 Swapo congress, declining to explicitly endorse candidates. In 2015, President Geingob asked Nujoma to serve on the new presidential advisory council.

* Adapted and updated from the Guide to Namibian Politics by Graham Hopwood

Comments

Namibian Sun

No comments have been left on this article