Landless in the Land of the Brave

Mabasa Sasa

At the close of Namibia’s ruling party Swapo’s fifth congress on 2 December 2012, party leader and state president at the time, Hifikepunye Pohamba, disclosed that a raft of major issues had been highlighted during deliberations and these would be dealt with expeditiously.

Among them were “accelerated land reform and land redistribution” and “addressing the access and affordability of residential land in urban and peri-urban areas”.

A few statistics will put the criticality of the land issue into perspective: White Namibians make up about 6% of Namibia’s population of 2.4 million people, other non-black groups (mostly mixed race) make up less than 8%, and the rest (about 76%) are black Africans.

But whites control nearly 90% of the land in what is the world’s 34th largest country by area. And around 50% of the arable land is in the hands of just about 4 000 white commercial farmers.

In this country of skewed land ownership, experts say the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in 2005 was US$2 334 (Africa’s average was US$681), but the richest 5% of the population – mostly whites – take about 71%.

At the same time, the poorest 55% account for 3% of GDP.

Unequal

This has seen Namibia characterised as one of the most unequal societies on earth, something that is rarely mentioned in the media. The whites who enjoy all this wealth are mostly descendants of German and South African colonisers, and many of them are absentee landowners who live permanently in South Africa, Italy, Germany and other places.

According to Dr Wolfgang Werner, who soon after Namibia’s independence in 1990 served as director of lands in the ministry of lands, resettlement and rehabilitation: “The racially-weighted distribution of land was an essential feature in the colonial exploitation of Namibia’s resources, directly affecting the profitability not only of settler agriculture, but also of mining and the industrial sector.

“As in pre-independence Zimbabwe, the whole wage structure and labour supply system depended critically on the land divisions in the country. Access to land determined the supply and cost of African labour to the colonial economy. So, large-scale dispossession of black Namibians was as much intended to provide white settlers with land as it was to deny black Namibians access to the same land, thereby denying them access to commercial agricultural production and forcing them into wage labour.”

The land issue

It is against this background that at its 2012 party congress, President Pohamba and Swapo included the land issue amongst the most pressing in Namibia. But how is it that this situation prevails 30 years after independence?

When apartheid South Africa finally succumbed to local military and international diplomatic pressure in 1990 and left Namibia, the new government tried to institute a process of land reform.

However, as in all independence pacts, crucial clauses were inserted in the constitution to ensure that “private property” remained protected and the status quo was preserved.

In Namibia’s case, this was Article 16(2) of Chapter 3 of the constitution, which says: “The state or a competent body or organ authorised by law may expropriate property in the public interest subject to the payment of just compensation, in accordance with requirements and procedures to be determined by [an] Act of Parliament.”

More broadly, this is interpreted as the ‘willing-buyer, willing-seller’ system, in which the state cannot acquire land for redistribution unless the landholder actually wants to let go of it. Crucially, the seller has to agree to the price offered by the government.

1% of land changed hands

This condition, it is widely accepted, came about as a result of the efforts of the ‘Contact Group’, which comprised the UK, USA, Canada, Germany and France, as a means of ensuring Swapo could not deliver on its key liberation grievance of large-scale land redistribution.

As such, between 1990 and 2002, only 1% of commercial land changed hands from whites to blacks, and by the mid-1990s, less than 20 freehold farms had been purchased for redistribution.

Available figures indicate that as at November 2011, the government had bought 293 farms covering some 1.8 million hectares at about US$66 million. This translated to 4 790 families resettled against a waiting-list of nearly 200 000. Namibia’s First National Development Plan (1995-2000) committed US$2.4 million per year for purchasing commercial farms, and a similar figure was set aside for the same purposes under the Second National Development Plan (2001-2005).

The annual budget for land acquisition was increased to US$5.9 million in 2003, and there are indications that this could soon be doubled. Even then, going by what was paid for 293 farms in the first 12 years of independence, the figure could turn out to be woefully inadequate as land prices rise.

Unlikely target

The government says it aims to acquire 15.3 million hectares of land by 2020; five million for direct resettlement and the rest through an Affirmative Action Loan Scheme. With the current pace of redistribution, such a target remains unlikely – unless radical reforms are instituted.

The government has responded to the land pressure by coming up with new regulations that it hopes will speed up the process of acquisition. However, it remains a willing-buyer, willing-seller system. In essence, the new model allows commercial farmers to tell the government they are not interested in selling land in a shorter space of time.

According to a newsletter by the lands and resettlement ministry (as it was called then), farmers can now withdraw their offer of selling land to the state if they do not like the initial offer price or how negotiations are proceeding. The government then moves on to the next farmer.

“This model opens the way for flexibility and negotiations between government and the landowner before the ministry makes a final counter-offer,” the lands ministry said.

Previously, once a farmer made an offer of sale to the state, s/he could not withdraw it and the two parties would be locked in never-ending negotiations with the Lands Tribunal standing available for price determination.

“The [new] mechanism has been rigorously tested since then and has proved to be doable and beneficial to all parties,” the lands ministry insisted.

Sabotage

This means farmers can easily price the land out of the government’s reach much quicker than previously, something that Namibia’s founding president, Dr Sam Nujoma, fumed about in an interview with the regional weekly paper, The Southern Times.

“We thought that when we have adopted the policy of national reconciliation, those whites who remained with us in Namibia, [would] also accept our policy of land reform, but we see now they are sabotaging land reform,” said a furious Nujoma at the time.

Land reform remains premised on the National Resettlement Policy and Resettlement criteria, which are thankfully now under review.

The criteria stem from the 1991 National Land Reform conference, which adopted 24 ‘consensus resolutions’ that inform the laws and policies governing tenure changes. Apart from the willing-buyer, willing-seller system, there can be no claims on the grounds of ‘ancestral land’ and priority is on expropriating farms from absentee landlords. Amendments through a proposed Land Bill, to peg maximum farm sizes in communal areas to 20 hectares and to identify under-utilised land among other measures, could also mean more people getting access to land. But the question is: Why are the farm sizes of the already disadvantaged being limited in a country where it is not unusual for a white farmer to own 20 000 or more hectares of land?

This article first appeared in the New African Magazine in 2013.

At the close of Namibia’s ruling party Swapo’s fifth congress on 2 December 2012, party leader and state president at the time, Hifikepunye Pohamba, disclosed that a raft of major issues had been highlighted during deliberations and these would be dealt with expeditiously.

Among them were “accelerated land reform and land redistribution” and “addressing the access and affordability of residential land in urban and peri-urban areas”.

A few statistics will put the criticality of the land issue into perspective: White Namibians make up about 6% of Namibia’s population of 2.4 million people, other non-black groups (mostly mixed race) make up less than 8%, and the rest (about 76%) are black Africans.

But whites control nearly 90% of the land in what is the world’s 34th largest country by area. And around 50% of the arable land is in the hands of just about 4 000 white commercial farmers.

In this country of skewed land ownership, experts say the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in 2005 was US$2 334 (Africa’s average was US$681), but the richest 5% of the population – mostly whites – take about 71%.

At the same time, the poorest 55% account for 3% of GDP.

Unequal

This has seen Namibia characterised as one of the most unequal societies on earth, something that is rarely mentioned in the media. The whites who enjoy all this wealth are mostly descendants of German and South African colonisers, and many of them are absentee landowners who live permanently in South Africa, Italy, Germany and other places.

According to Dr Wolfgang Werner, who soon after Namibia’s independence in 1990 served as director of lands in the ministry of lands, resettlement and rehabilitation: “The racially-weighted distribution of land was an essential feature in the colonial exploitation of Namibia’s resources, directly affecting the profitability not only of settler agriculture, but also of mining and the industrial sector.

“As in pre-independence Zimbabwe, the whole wage structure and labour supply system depended critically on the land divisions in the country. Access to land determined the supply and cost of African labour to the colonial economy. So, large-scale dispossession of black Namibians was as much intended to provide white settlers with land as it was to deny black Namibians access to the same land, thereby denying them access to commercial agricultural production and forcing them into wage labour.”

The land issue

It is against this background that at its 2012 party congress, President Pohamba and Swapo included the land issue amongst the most pressing in Namibia. But how is it that this situation prevails 30 years after independence?

When apartheid South Africa finally succumbed to local military and international diplomatic pressure in 1990 and left Namibia, the new government tried to institute a process of land reform.

However, as in all independence pacts, crucial clauses were inserted in the constitution to ensure that “private property” remained protected and the status quo was preserved.

In Namibia’s case, this was Article 16(2) of Chapter 3 of the constitution, which says: “The state or a competent body or organ authorised by law may expropriate property in the public interest subject to the payment of just compensation, in accordance with requirements and procedures to be determined by [an] Act of Parliament.”

More broadly, this is interpreted as the ‘willing-buyer, willing-seller’ system, in which the state cannot acquire land for redistribution unless the landholder actually wants to let go of it. Crucially, the seller has to agree to the price offered by the government.

1% of land changed hands

This condition, it is widely accepted, came about as a result of the efforts of the ‘Contact Group’, which comprised the UK, USA, Canada, Germany and France, as a means of ensuring Swapo could not deliver on its key liberation grievance of large-scale land redistribution.

As such, between 1990 and 2002, only 1% of commercial land changed hands from whites to blacks, and by the mid-1990s, less than 20 freehold farms had been purchased for redistribution.

Available figures indicate that as at November 2011, the government had bought 293 farms covering some 1.8 million hectares at about US$66 million. This translated to 4 790 families resettled against a waiting-list of nearly 200 000. Namibia’s First National Development Plan (1995-2000) committed US$2.4 million per year for purchasing commercial farms, and a similar figure was set aside for the same purposes under the Second National Development Plan (2001-2005).

The annual budget for land acquisition was increased to US$5.9 million in 2003, and there are indications that this could soon be doubled. Even then, going by what was paid for 293 farms in the first 12 years of independence, the figure could turn out to be woefully inadequate as land prices rise.

Unlikely target

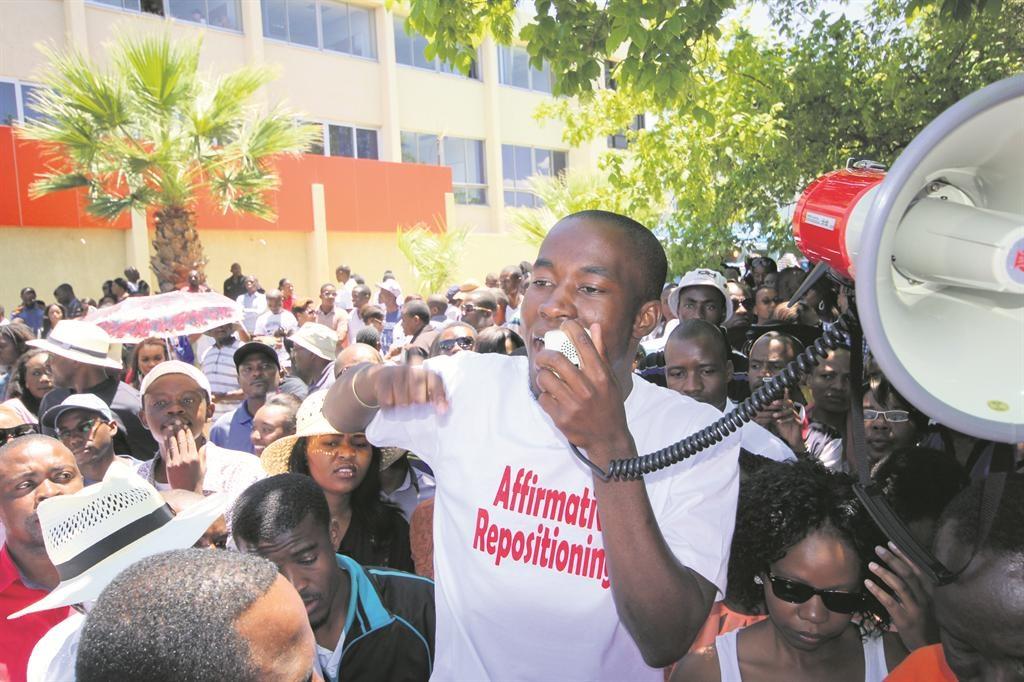

The government says it aims to acquire 15.3 million hectares of land by 2020; five million for direct resettlement and the rest through an Affirmative Action Loan Scheme. With the current pace of redistribution, such a target remains unlikely – unless radical reforms are instituted.

The government has responded to the land pressure by coming up with new regulations that it hopes will speed up the process of acquisition. However, it remains a willing-buyer, willing-seller system. In essence, the new model allows commercial farmers to tell the government they are not interested in selling land in a shorter space of time.

According to a newsletter by the lands and resettlement ministry (as it was called then), farmers can now withdraw their offer of selling land to the state if they do not like the initial offer price or how negotiations are proceeding. The government then moves on to the next farmer.

“This model opens the way for flexibility and negotiations between government and the landowner before the ministry makes a final counter-offer,” the lands ministry said.

Previously, once a farmer made an offer of sale to the state, s/he could not withdraw it and the two parties would be locked in never-ending negotiations with the Lands Tribunal standing available for price determination.

“The [new] mechanism has been rigorously tested since then and has proved to be doable and beneficial to all parties,” the lands ministry insisted.

Sabotage

This means farmers can easily price the land out of the government’s reach much quicker than previously, something that Namibia’s founding president, Dr Sam Nujoma, fumed about in an interview with the regional weekly paper, The Southern Times.

“We thought that when we have adopted the policy of national reconciliation, those whites who remained with us in Namibia, [would] also accept our policy of land reform, but we see now they are sabotaging land reform,” said a furious Nujoma at the time.

Land reform remains premised on the National Resettlement Policy and Resettlement criteria, which are thankfully now under review.

The criteria stem from the 1991 National Land Reform conference, which adopted 24 ‘consensus resolutions’ that inform the laws and policies governing tenure changes. Apart from the willing-buyer, willing-seller system, there can be no claims on the grounds of ‘ancestral land’ and priority is on expropriating farms from absentee landlords. Amendments through a proposed Land Bill, to peg maximum farm sizes in communal areas to 20 hectares and to identify under-utilised land among other measures, could also mean more people getting access to land. But the question is: Why are the farm sizes of the already disadvantaged being limited in a country where it is not unusual for a white farmer to own 20 000 or more hectares of land?

This article first appeared in the New African Magazine in 2013.

Comments

Namibian Sun

No comments have been left on this article