Flushing tax dollars

Ombudsman John Walters has called for an investigation into public entities’ failure to submit annual financial reports.

Jo-Maré Duddy – A request by the Office of the Ombudsman to access the financial statements or audit reports of government-owned August 26 was dismissed by defence minister Peter Vilho, stating that “information about the activities and installations of the security sector has become a free-for-all”.

A new report by the ombudsman doesn’t just echo analysts’ growing frustration with tax dollars not properly accounted for in public, but also show how the red tape involved in getting reliable and timely information.

August 26 Holding Company, owned by the ministry of defence on behalf of government, hasn’t submitted annual financial reports since its incorporation in August 1998. As part of the defence ministry, August 26 has access to millions of taxpayers’ money with defence getting one of the biggest chunks of the budget every year, a lot of it classified spending.

Ombudsman John Walters has been trying to get information about the financial affairs of August 26 since May 2018, following a complaint by the official opposition party, the Popular Democratic Movement (PDM).

Early in 2019, he decided to extend his investigation to cover the compliance of all public enterprises (PEs) to submit annual financial statements. PEs or state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are required by law to submit an annual report to its portfolio minister not later than six months after the end of each financial year.

‘SUSPECT’

Walters said he extended the investigation because he had “reason to suspect that powers, duties or functions which vest in the state, boards or public enterprises are either performed in an irregular manner or are not exercised or performed at all.”

These responsibilities vary from performance agreements and financial reports to governance agreements with individual board members of PEs.

In a report compiled on the investigation, Walters recommended that public enterprise minister Leon Jooste “takes appropriate actions or steps to remedy or correct these matters by directing a special investigation to be conducted in relation to above failings and other matters concerning the business, trade, dealings, affairs, assets or liabilities of the defaulting public enterprises … and inform the ombudsman and the public on the outcome of the investigation.”

Following no response from Jooste, Walters submitted his report in parliament at the end of September.

MURKY

Walters’ concern is repeated in a report by the Institute of Public Policy Research (IPPR) which shows no public information whatsoever is available for more than a third of monitored PEs in Namibia.

According to the IPPR’s Public Enterprise Annual Rankings, published in March, full annual reports of only 12 PEs have been public so far.

The IPPR scored PEs out of a possible 100 points. The following PEs got less than 50: Namibia Development Corporation (47), Offshore Development Corporation (47), Fishcor (45), Roads Authority (45), Epangelo Mining (30), TransNamib (30), Namibia Wildlife Resorts (25), Lüderitz Waterfront (15), Air Namibia (10), Henties Bay Waterfront (5), Zambezi Waterfront (0) and Roads Contractor Company (0).

Of the above, recent financial or audit reports were only available for the Namibia Development Corporation or NDC (2014-2017), Fishcor (2016/17), Roads Authority (2016/17), and TransNamib (2013).

According to the IPPR, allegations of mismanagement or corruption have been investigated at nine PEs tracked by the institute.

STONEWALLED

Ombudsman Walters’ report shows just how difficult it is to get information on PEs.

Following the request in May 2018 and Vilho’s subsequent refusal to provide financial reports, Walters visited auditor general Junias Kandjeke in June that year. Kandjeke informed him that PEs don’t fall under his audit jurisdiction.

Walters then went to Jooste. The visit in October 2018 “proved to be fruitless as he could not assist us in the investigation”, Walters said in his report.

He continued: “I was discouraged by this temporary setback and I put the investigation on hold in order to concentrate on other duties.”

In 2019, Walters started investigating all PEs in terms of compliance.

In a conversation during February 2019, Walters asked former justice minister Sacky Shanghala – now one of the accused in the Fishrot scandal – to help him to access the offices and financial statements of August 26.

On 9 August last year, Shanghala wrote to Walters regarding “the negative attitude” the ombudsman received from Vilho.

Shanghala said he understood the “sensitive nature of the industry within which August 26 (Pty) Ltd operates and the sensitivity attached to the wanton access to the information such an entity may contain”. However, he also “lament the fact that the ombudsman as a constitutional institution requires the support of all government officials in the performance of his functions”.

Shanghala undertook to “endeavour to consult” his “colleagues” – the director general of the Namibia Central Intelligence Service (NCIS), Phillemon Malima, and the then minister of defence, Penda Ya Ndakolo – “for an urgent meeting to be able to prepare for the relevant consultation” Walters needed. He asked Walters what questions he had about August 26.

Prime minister Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila and then minister in the presidency, Martin Andjaba, as well as Ya Ndakolo and Malima received copies of Shanghala’s letter.

On 16 August, Walters responded to Shanghala’s letter, informing him that he wanted the annual reports of August 26 for the past five years, as well as a list of all its subsidiaries and names of companies in which August 26 is a shareholder.

He received no response and sent a follow-up letter on 24 September.

BACK TO DRAWING BOARD

By now Walters had received a 28-page list from the National Assembly with PEs which tabled annual reports from 2010 to 2019.

On 24 October 2019, he once again wrote to Jooste, attaching a list of PEs which failed to submit reports. Walters wanted Jooste to ask the portfolio ministers why the PEs resorting under their ministries did not submit the reports.

Jooste’s office responded on 31 October, only providing a list of PEs which submitted annual reports to the ministry of public enterprises.

On 11 May this year, Walters sent an e-mail to Jooste’s office stating he was still waiting for a promised report on the matter. He requested a meeting with Jooste. Walters got feedback the same day, saying “a response to your request will be communicated accordingly”.

However, Walters received no other response from Jooste’s office.

On 8 September, Walters’ report on August 26 and other PEs was hand-delivered to Jooste’s office. The Ombudsman requested the minister’s response by 26 September so that it could be included in his report.

Jooste’s office neither acknowledge receipt of the report, nor responded. As a result, Walters tabled the report in parliament without Jooste’s feedback.

Walters said in his report: “The Ombudsman Act is silent on what the National Assembly should do with the ombudsman’s reports, but Rule 70(3) of the Standing Rules and Orders of the National Assembly mandates the Parliamentary [Committee] on Constitutional and Legal Affairs to (may) consider, examine, report on, and make the necessary recommendations to the National Assembly.”

AUGUST 26

August 26’s interests vary from the manufacturing of combat vehicles to long-term insurance, textile manufacturing, construction and logistics, as well as farming and leisure.

The PDM’s complaint lodged at the ombudsman stated that “August 26 has been immune to public scrutiny and internationally recognised standards of accounting and reporting, as the enterprise has neither appeared before the Standing Committee on Public Accounts, and neither is audited by the auditor general”.

“This is despite the fact that August 26 or its subsidiaries have been recipients of multimillion-dollar government contracts,” the PDM claimed.

“If in fact the auditor general has carried out an audit at August 26, these reports have not been publically disclosed,” the political party said.

In his response letter to Walters in July 2018, Vilho (then the executive director of defence) said: “PDM being a political party with representation in parliament should raise the issue in parliament where it could be properly and adequately addressed and not through your office.”

‘ALL AND SUNDRY’

Vilho continued that the defence sector “has in recent times been inundated with requests for all kind of information by all and sundry in the name of transparency and freedom of speech”. “Coming even from those entities whose motive is nothing but commercial,” he added.

According to Vilho: “The defence sector is a prime target for hostile intelligence activities, including those of notional friends and allies, and needs to take steps to protect itself and its information. Unlike with other SOEs, the activities of the defence force and its industries cannot be clinically detached.”

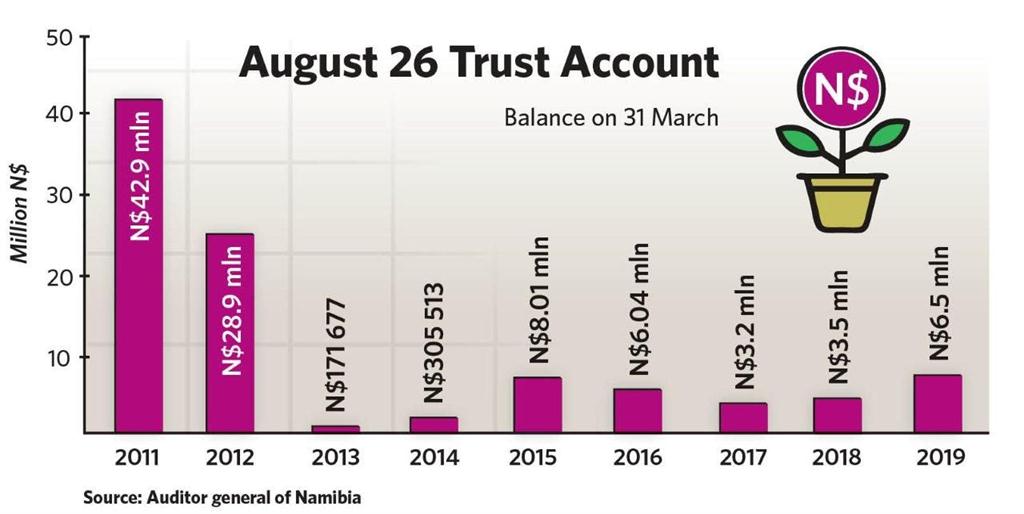

The only reference to August 26 in the auditor general’s reports on the ministry of defence is that of a trust account at a local commercial bank. (See table.)

On at least two occasions this account was part of the basis of auditor general’s qualified opinion on the financial statements of defence. The closing balances of the account could not be verified as the bank statements were not submitted for auditing purposes.

‘EAT THIS MONEY’

Vilho last week told Nampa there is no systemic corruption in the ministry or August 26.

He said antagonists have made it their priority to brand the defence ministry, NDF or companies linked to it as corrupt.

“The picture they are trying to paint is that we sit at the table, starting from the minister, my subordinates and people from August 26 and discuss how we are going to 'eat this money',” he said.

He also dismissed claims by the public that August 26 and its 11 subsidiaries were not being audited.

He said the audited financial statements are not for public consumption.

“We use those audit reports for our own internal controls so that we make sure that money is accounted for.”

Vilho maintained: “What they want is to have access to those reports. But we can’t give them those reports because they not only speak to the amounts of monies used, but they also speak of what the money was used for and that’s what we’re saying is confidential.”

Asked if this means everything pertaining to August 26 is off limits, he replied using an example.

He said politicians or the public may want to know how much ammunition the Namibian Defence Force’s Seventh Brigade has or how much is spent on the ammunition factory.

It might not occur to civilians how dangerous it is to reveal such information, Vilho said.

“All those things are interrelated because people in the military world can make an analysis from that information, they can then understand what your capacity to produce ammunition is, how much you produce a day and so on. This is the tricky part that people normally don’t understand,” he told Nampa.

[email protected]

A new report by the ombudsman doesn’t just echo analysts’ growing frustration with tax dollars not properly accounted for in public, but also show how the red tape involved in getting reliable and timely information.

August 26 Holding Company, owned by the ministry of defence on behalf of government, hasn’t submitted annual financial reports since its incorporation in August 1998. As part of the defence ministry, August 26 has access to millions of taxpayers’ money with defence getting one of the biggest chunks of the budget every year, a lot of it classified spending.

Ombudsman John Walters has been trying to get information about the financial affairs of August 26 since May 2018, following a complaint by the official opposition party, the Popular Democratic Movement (PDM).

Early in 2019, he decided to extend his investigation to cover the compliance of all public enterprises (PEs) to submit annual financial statements. PEs or state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are required by law to submit an annual report to its portfolio minister not later than six months after the end of each financial year.

‘SUSPECT’

Walters said he extended the investigation because he had “reason to suspect that powers, duties or functions which vest in the state, boards or public enterprises are either performed in an irregular manner or are not exercised or performed at all.”

These responsibilities vary from performance agreements and financial reports to governance agreements with individual board members of PEs.

In a report compiled on the investigation, Walters recommended that public enterprise minister Leon Jooste “takes appropriate actions or steps to remedy or correct these matters by directing a special investigation to be conducted in relation to above failings and other matters concerning the business, trade, dealings, affairs, assets or liabilities of the defaulting public enterprises … and inform the ombudsman and the public on the outcome of the investigation.”

Following no response from Jooste, Walters submitted his report in parliament at the end of September.

MURKY

Walters’ concern is repeated in a report by the Institute of Public Policy Research (IPPR) which shows no public information whatsoever is available for more than a third of monitored PEs in Namibia.

According to the IPPR’s Public Enterprise Annual Rankings, published in March, full annual reports of only 12 PEs have been public so far.

The IPPR scored PEs out of a possible 100 points. The following PEs got less than 50: Namibia Development Corporation (47), Offshore Development Corporation (47), Fishcor (45), Roads Authority (45), Epangelo Mining (30), TransNamib (30), Namibia Wildlife Resorts (25), Lüderitz Waterfront (15), Air Namibia (10), Henties Bay Waterfront (5), Zambezi Waterfront (0) and Roads Contractor Company (0).

Of the above, recent financial or audit reports were only available for the Namibia Development Corporation or NDC (2014-2017), Fishcor (2016/17), Roads Authority (2016/17), and TransNamib (2013).

According to the IPPR, allegations of mismanagement or corruption have been investigated at nine PEs tracked by the institute.

STONEWALLED

Ombudsman Walters’ report shows just how difficult it is to get information on PEs.

Following the request in May 2018 and Vilho’s subsequent refusal to provide financial reports, Walters visited auditor general Junias Kandjeke in June that year. Kandjeke informed him that PEs don’t fall under his audit jurisdiction.

Walters then went to Jooste. The visit in October 2018 “proved to be fruitless as he could not assist us in the investigation”, Walters said in his report.

He continued: “I was discouraged by this temporary setback and I put the investigation on hold in order to concentrate on other duties.”

In 2019, Walters started investigating all PEs in terms of compliance.

In a conversation during February 2019, Walters asked former justice minister Sacky Shanghala – now one of the accused in the Fishrot scandal – to help him to access the offices and financial statements of August 26.

On 9 August last year, Shanghala wrote to Walters regarding “the negative attitude” the ombudsman received from Vilho.

Shanghala said he understood the “sensitive nature of the industry within which August 26 (Pty) Ltd operates and the sensitivity attached to the wanton access to the information such an entity may contain”. However, he also “lament the fact that the ombudsman as a constitutional institution requires the support of all government officials in the performance of his functions”.

Shanghala undertook to “endeavour to consult” his “colleagues” – the director general of the Namibia Central Intelligence Service (NCIS), Phillemon Malima, and the then minister of defence, Penda Ya Ndakolo – “for an urgent meeting to be able to prepare for the relevant consultation” Walters needed. He asked Walters what questions he had about August 26.

Prime minister Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila and then minister in the presidency, Martin Andjaba, as well as Ya Ndakolo and Malima received copies of Shanghala’s letter.

On 16 August, Walters responded to Shanghala’s letter, informing him that he wanted the annual reports of August 26 for the past five years, as well as a list of all its subsidiaries and names of companies in which August 26 is a shareholder.

He received no response and sent a follow-up letter on 24 September.

BACK TO DRAWING BOARD

By now Walters had received a 28-page list from the National Assembly with PEs which tabled annual reports from 2010 to 2019.

On 24 October 2019, he once again wrote to Jooste, attaching a list of PEs which failed to submit reports. Walters wanted Jooste to ask the portfolio ministers why the PEs resorting under their ministries did not submit the reports.

Jooste’s office responded on 31 October, only providing a list of PEs which submitted annual reports to the ministry of public enterprises.

On 11 May this year, Walters sent an e-mail to Jooste’s office stating he was still waiting for a promised report on the matter. He requested a meeting with Jooste. Walters got feedback the same day, saying “a response to your request will be communicated accordingly”.

However, Walters received no other response from Jooste’s office.

On 8 September, Walters’ report on August 26 and other PEs was hand-delivered to Jooste’s office. The Ombudsman requested the minister’s response by 26 September so that it could be included in his report.

Jooste’s office neither acknowledge receipt of the report, nor responded. As a result, Walters tabled the report in parliament without Jooste’s feedback.

Walters said in his report: “The Ombudsman Act is silent on what the National Assembly should do with the ombudsman’s reports, but Rule 70(3) of the Standing Rules and Orders of the National Assembly mandates the Parliamentary [Committee] on Constitutional and Legal Affairs to (may) consider, examine, report on, and make the necessary recommendations to the National Assembly.”

AUGUST 26

August 26’s interests vary from the manufacturing of combat vehicles to long-term insurance, textile manufacturing, construction and logistics, as well as farming and leisure.

The PDM’s complaint lodged at the ombudsman stated that “August 26 has been immune to public scrutiny and internationally recognised standards of accounting and reporting, as the enterprise has neither appeared before the Standing Committee on Public Accounts, and neither is audited by the auditor general”.

“This is despite the fact that August 26 or its subsidiaries have been recipients of multimillion-dollar government contracts,” the PDM claimed.

“If in fact the auditor general has carried out an audit at August 26, these reports have not been publically disclosed,” the political party said.

In his response letter to Walters in July 2018, Vilho (then the executive director of defence) said: “PDM being a political party with representation in parliament should raise the issue in parliament where it could be properly and adequately addressed and not through your office.”

‘ALL AND SUNDRY’

Vilho continued that the defence sector “has in recent times been inundated with requests for all kind of information by all and sundry in the name of transparency and freedom of speech”. “Coming even from those entities whose motive is nothing but commercial,” he added.

According to Vilho: “The defence sector is a prime target for hostile intelligence activities, including those of notional friends and allies, and needs to take steps to protect itself and its information. Unlike with other SOEs, the activities of the defence force and its industries cannot be clinically detached.”

The only reference to August 26 in the auditor general’s reports on the ministry of defence is that of a trust account at a local commercial bank. (See table.)

On at least two occasions this account was part of the basis of auditor general’s qualified opinion on the financial statements of defence. The closing balances of the account could not be verified as the bank statements were not submitted for auditing purposes.

‘EAT THIS MONEY’

Vilho last week told Nampa there is no systemic corruption in the ministry or August 26.

He said antagonists have made it their priority to brand the defence ministry, NDF or companies linked to it as corrupt.

“The picture they are trying to paint is that we sit at the table, starting from the minister, my subordinates and people from August 26 and discuss how we are going to 'eat this money',” he said.

He also dismissed claims by the public that August 26 and its 11 subsidiaries were not being audited.

He said the audited financial statements are not for public consumption.

“We use those audit reports for our own internal controls so that we make sure that money is accounted for.”

Vilho maintained: “What they want is to have access to those reports. But we can’t give them those reports because they not only speak to the amounts of monies used, but they also speak of what the money was used for and that’s what we’re saying is confidential.”

Asked if this means everything pertaining to August 26 is off limits, he replied using an example.

He said politicians or the public may want to know how much ammunition the Namibian Defence Force’s Seventh Brigade has or how much is spent on the ammunition factory.

It might not occur to civilians how dangerous it is to reveal such information, Vilho said.

“All those things are interrelated because people in the military world can make an analysis from that information, they can then understand what your capacity to produce ammunition is, how much you produce a day and so on. This is the tricky part that people normally don’t understand,” he told Nampa.

[email protected]

Comments

Namibian Sun

No comments have been left on this article