Civil service wage bill a conundrum

The size of the civil service might be a fiscal drain, but is also alleviated unemployment and drives the economy.

Jo-Maré Duddy – When finance minister Calle Schlettwein tables his 2018/19 Main Budget – widely expected towards the end of this month – containing expenditure on the civil service will be one of his biggest challenges.

“Scaling back on government jobs is no easy feat,” Dylan van Wyk, senior analyst at Cirrus Capital, says.

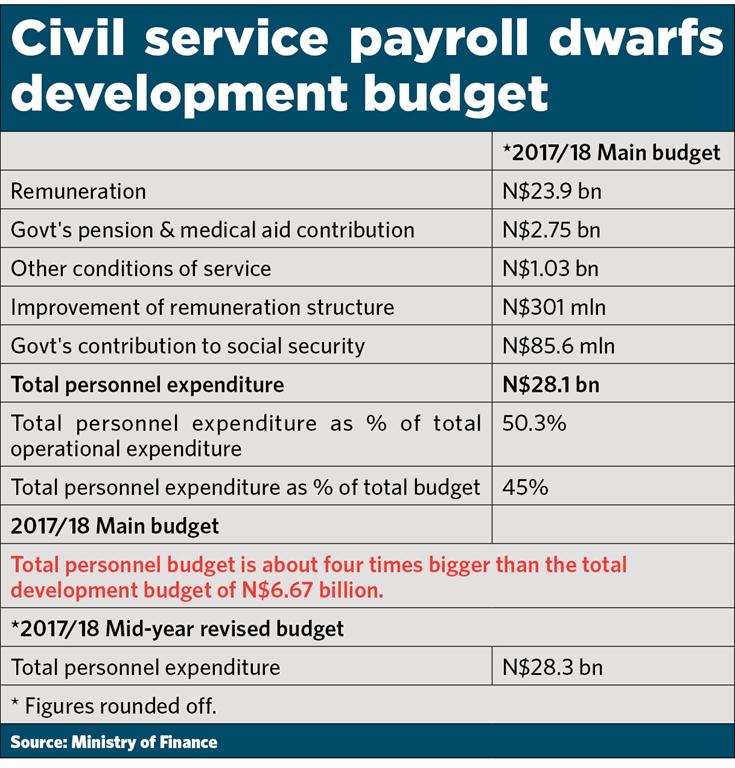

According to the 2017/18 Main Budget tabled last March, about N$28.1 billion was set aside for the total remuneration of the civil service in the current budget year, which ends on 31 March 2018. This amount was increased to about N$28.3 billion in the Mid-Year Budget Review. In the same document, total expenditure on the wage bill in 2018/19 was estimated at approximately N$28.4 billion.

Market Watch approached local analysts on the conundrum Schlettwein faces: The ballooning remuneration roll of civil servants is unsustainable, a fact acknowledged by the minister and economists alike. However, shrinking the size of the civil service comes with its own set of major sosio-economic and economic consequences.

Namibia’s personnel expenditure stood at 43% of total expenditure and at 48% of operational expenditure in 2017/18, says Indileni Nanghonga, junior analyst at Simonis Storm. “The public sector wage bill has increasingly crowded out other areas of spending.”

“The civil service is an extremely thorny issue,” Van Wyk says.

Redundancies in the civil service will result in early retrenchment packages. This is a costly exercise in the short term, but will bring long-term savings, Van Wyk says.

Unemployment

“This exercise would likely result in a structural increase in unemployment as many of these redundancies may find it difficult to find work in the private sector,” he says. Namibia ‘s large defense force is a prime example, as these individuals have quite a specific skill set, he adds.

Nanghonga points out that freezing new appointments in the civil services – something Schlettwein has already committed to – will equally affect unemployment in the country. “We believe that this will add to the already high youth unemployment statistics, but is a necessary measure in consolidating the fiscal position,” she says.

According to the Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA), the unemployment rate in 2016 was 34%, up from 27.9% in 2014. The country’s youth unemployment rate was 43.4% compared to 39% in 2014.

“Government is the biggest employer and on the back of that, frozen vacancies will lead to higher youth unemployment. We estimate the civil servants to be around 120 000, versus a workforce of 708 895. This means that 17% of workers are civil servants,” Nanghonga says.

Van Wyk says the suggestion of freezing posts and limiting salary increases is a “more palatable option”.

“In essence, this will allow the country to grow into its overinflated budget. This will avoid the sudden shock to the economy of removing thousands of jobs.”

This strategy, however, runs the risk of doing too little too late, and our budget deficit may not be reeled in as quickly as anticipated, Van Wyk says.

“Fiscal consolidation may thus become a five to ten-year exercise. Additionally, this does not address the issue of labour unions, and government will likely succumb to a round of salary increases should the unions go on strike,” he continues.

Spending power

Should the government opt for retrenchments, the issue of civil servants’ personal spending power and its impact on the economy needs to be considered.

“Many of these workers have a high number of dependants, which will mean these layoffs will have serious negative repercussions, especially in sectors such as the retail and wholesale,” Van Wyk points out.

According to the NSA’s Namibia Inter-censal Demographic Survey 2016 Report, the average national household size is 3.9. Regional averages, however, range from 2.1 to 5.2.

Nanghonga says consumer spending is a vital economic aspect because it usually coincides with the overall consumer confidence in a nation’s economy. “Furthermore, businesses use consumer spending data in their supply and demand calculations. This helps businesses produce goods or services at the most constructive consumer price.”

The Bank of Namibia (BoN), in its latest Economic Outlook released in December, predicted that wholesale and retail trade spent 2017 in recession, with expected growth of -6.4%. It forecast a recession for this year too, with growth of -1.5% foreseen.

The solution

The government needs to audit its payroll to ensure that only legally-hired employees are paid a salary, Nanghonga says.

“Ghost workers must be eliminated and stronger governance reforms to avoid wastages. This can be achieved by reforming our salary system to make it bearable and well-matched with the country’ long-run developmental plans.”

Van Wyk says “there is still some room for immediate savings by investigating issues such as ‘ghost employees’ and issues where workers are being overcompensated for their position”. However, this will not alleviate the bigger problem over an oversized workforce, he stresses.

According to Nanghonga, budgets to ministries should be managed within “clear, credible and predictable limits” and ministers should be accountable for maladministration that occurs under their ministry.

“Budget execution should be actively calculated, managed and scrutinised. In addition, performance, evaluation and value for money should be integral to the budget execution process,” she says.

Van Wyk points out that the issue of the wage bill is a “challenge that has been a very long time in the making and there are no quick fixes”.

“The normalisation of the wage bill, by means of lower-than-inflation salary increases combined with the natural attrition of the workforce as people retire will take years to achieve the goal of a sustainable wage bill, but what other alternatives are there?” he says.

“Scaling back on government jobs is no easy feat,” Dylan van Wyk, senior analyst at Cirrus Capital, says.

According to the 2017/18 Main Budget tabled last March, about N$28.1 billion was set aside for the total remuneration of the civil service in the current budget year, which ends on 31 March 2018. This amount was increased to about N$28.3 billion in the Mid-Year Budget Review. In the same document, total expenditure on the wage bill in 2018/19 was estimated at approximately N$28.4 billion.

Market Watch approached local analysts on the conundrum Schlettwein faces: The ballooning remuneration roll of civil servants is unsustainable, a fact acknowledged by the minister and economists alike. However, shrinking the size of the civil service comes with its own set of major sosio-economic and economic consequences.

Namibia’s personnel expenditure stood at 43% of total expenditure and at 48% of operational expenditure in 2017/18, says Indileni Nanghonga, junior analyst at Simonis Storm. “The public sector wage bill has increasingly crowded out other areas of spending.”

“The civil service is an extremely thorny issue,” Van Wyk says.

Redundancies in the civil service will result in early retrenchment packages. This is a costly exercise in the short term, but will bring long-term savings, Van Wyk says.

Unemployment

“This exercise would likely result in a structural increase in unemployment as many of these redundancies may find it difficult to find work in the private sector,” he says. Namibia ‘s large defense force is a prime example, as these individuals have quite a specific skill set, he adds.

Nanghonga points out that freezing new appointments in the civil services – something Schlettwein has already committed to – will equally affect unemployment in the country. “We believe that this will add to the already high youth unemployment statistics, but is a necessary measure in consolidating the fiscal position,” she says.

According to the Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA), the unemployment rate in 2016 was 34%, up from 27.9% in 2014. The country’s youth unemployment rate was 43.4% compared to 39% in 2014.

“Government is the biggest employer and on the back of that, frozen vacancies will lead to higher youth unemployment. We estimate the civil servants to be around 120 000, versus a workforce of 708 895. This means that 17% of workers are civil servants,” Nanghonga says.

Van Wyk says the suggestion of freezing posts and limiting salary increases is a “more palatable option”.

“In essence, this will allow the country to grow into its overinflated budget. This will avoid the sudden shock to the economy of removing thousands of jobs.”

This strategy, however, runs the risk of doing too little too late, and our budget deficit may not be reeled in as quickly as anticipated, Van Wyk says.

“Fiscal consolidation may thus become a five to ten-year exercise. Additionally, this does not address the issue of labour unions, and government will likely succumb to a round of salary increases should the unions go on strike,” he continues.

Spending power

Should the government opt for retrenchments, the issue of civil servants’ personal spending power and its impact on the economy needs to be considered.

“Many of these workers have a high number of dependants, which will mean these layoffs will have serious negative repercussions, especially in sectors such as the retail and wholesale,” Van Wyk points out.

According to the NSA’s Namibia Inter-censal Demographic Survey 2016 Report, the average national household size is 3.9. Regional averages, however, range from 2.1 to 5.2.

Nanghonga says consumer spending is a vital economic aspect because it usually coincides with the overall consumer confidence in a nation’s economy. “Furthermore, businesses use consumer spending data in their supply and demand calculations. This helps businesses produce goods or services at the most constructive consumer price.”

The Bank of Namibia (BoN), in its latest Economic Outlook released in December, predicted that wholesale and retail trade spent 2017 in recession, with expected growth of -6.4%. It forecast a recession for this year too, with growth of -1.5% foreseen.

The solution

The government needs to audit its payroll to ensure that only legally-hired employees are paid a salary, Nanghonga says.

“Ghost workers must be eliminated and stronger governance reforms to avoid wastages. This can be achieved by reforming our salary system to make it bearable and well-matched with the country’ long-run developmental plans.”

Van Wyk says “there is still some room for immediate savings by investigating issues such as ‘ghost employees’ and issues where workers are being overcompensated for their position”. However, this will not alleviate the bigger problem over an oversized workforce, he stresses.

According to Nanghonga, budgets to ministries should be managed within “clear, credible and predictable limits” and ministers should be accountable for maladministration that occurs under their ministry.

“Budget execution should be actively calculated, managed and scrutinised. In addition, performance, evaluation and value for money should be integral to the budget execution process,” she says.

Van Wyk points out that the issue of the wage bill is a “challenge that has been a very long time in the making and there are no quick fixes”.

“The normalisation of the wage bill, by means of lower-than-inflation salary increases combined with the natural attrition of the workforce as people retire will take years to achieve the goal of a sustainable wage bill, but what other alternatives are there?” he says.

Comments

Namibian Sun

No comments have been left on this article